Nearly 40 percent of American women between the ages of 15 and 44 say they would like to leave the United States and live elsewhere permanently, according to a recent Gallup poll.

These are not people disengaging from society or opting out of adulthood. They are women in the years when people typically build careers, raise children, care for family members, and anchor communities. They are doing the work that keeps economies and households functioning.

When this many women begin imagining a future somewhere else, it signals something larger than dissatisfaction. It suggests a recalibration of what feels livable over the long term.

Not because everything is broken.

But because too much feels precarious.

Gallup’s data adds an important layer. The desire to leave cuts across marital status and family structure. Women with children report nearly the same interest in leaving as women without them. Married and single women show similar patterns. This is not a niche reaction to one issue. It is a broad response to lived conditions.

Forty percent does not mean forty percent are leaving. It means forty percent are pausing long enough to ask whether staying will keep working.

That pause matters.

A Reassessment of Quality of Life Is Underway

For years, conversations about leaving the United States were framed as ideological or exceptional. Leaving was something people did because of politics, wanderlust, or a dramatic personal rupture.

What feels different now is how ordinary the questions have become.

They show up in small moments. Scheduling a doctor’s appointment. Looking at a childcare invoice. Calculating whether another year of this pace is sustainable. Wondering how much resilience is reasonable to ask of one household.

Quality of life has stopped being an abstract preference and become a structural question. It is about whether the systems people rely on reduce stress or compound it.

- Healthcare

- Work expectations

- Caregiving support

- Safety

- Legal stability

These are not luxury concerns, they are the scaffolding of daily life.

Healthcare and the Cost of Constant Vigilance

Healthcare sits at the center of this reassessment for a reason.

The United States spends more on healthcare than any other high-income country. According to the OECD health spending data, the U.S. devotes over 16 percent of its GDP to healthcare, far above peer nations. Yet higher spending has not translated into greater financial security for patients.

Research from the Kaiser Family Foundation shows that roughly four in ten U.S. adults carry some form of medical debt, and many delay or forgo care because of cost. This is not limited to the uninsured. Even families with employer-sponsored coverage report significant financial strain after medical events.

The impact is not just financial. It is psychological.

Healthcare becomes something to manage strategically rather than something to trust. Every decision is filtered through coverage, deductibles, and risk. Over time, that vigilance becomes exhausting.

In countries with universal healthcare or universal accident coverage, the underlying assumption is different. Illness and injury are treated as expected parts of life rather than personal financial failures. The result is not perfection, but predictability.

For women coordinating care for children, partners, and aging parents, predictability is not a minor benefit. It shapes whether life feels manageable.

Healthcare systems do not just treat bodies. They determine how safe it feels to plan a life.

Childcare and the Hidden Economics of Care

Childcare is another pressure point quietly shaping this conversation.

According to the U.S. Department of Labor’s childcare cost data, families spend between 9 and 16 percent of median household income on childcare for one child, depending on location and care type. For families with multiple children, the math quickly becomes untenable.

This reality affects women disproportionately. Numerous labor studies show that childcare costs are a primary reason women reduce hours or exit the workforce, even when they want to continue working. Over time, these interruptions compound into lower lifetime earnings and reduced retirement security.

In countries where childcare is subsidized or integrated into public systems, caregiving is treated as infrastructure rather than a private problem. Parents still make trade-offs, but the margins are wider. One system failure does not collapse the entire household budget.

When women imagine life elsewhere, they are often imagining a place where care work does not automatically derail everything else.

Maternal Health as a Measure of System Trust

Maternal health outcomes offer one of the clearest indicators of how well a society supports women during periods of vulnerability.

The United States has one of the highest maternal mortality rates among high-income countries. According to the Commonwealth Fund’s international comparison, the U.S. records far more maternal deaths per 100,000 live births than peer nations.

The disparities are especially stark. CDC maternal mortality data shows that Black women in the U.S. experience maternal death at more than twice the rate of white women, regardless of income or education.

These numbers do more than describe outcomes. They shape perception. They influence whether pregnancy feels safe. They affect whether people trust the healthcare system during moments when trust matters most.

For many women, this knowledge becomes part of the background when imagining where they want to live and raise families.

Safety and the Emotional Baseline of Daily Life

Safety is often discussed in statistics, but its impact is deeply emotional.

In the United States, firearm injury remains a leading cause of death among children and adolescents, according to CDC injury data. Even for families who are never directly affected, the awareness of this reality shapes behavior. School drills. Public alerts. The constant sense that ordinary spaces require vigilance.

Over time, that vigilance becomes normalized.

In countries with stricter gun regulations, parents often describe a different emotional baseline. Schools feel calmer. Public spaces feel more predictable. The mental energy spent scanning for danger recedes.

This does not mean other societies are free of fear or violence. It means the emotional tax is lower. And when people are deciding where to raise children, emotional tax matters.

Work, Rest, and the Sustainability Question

Work culture is another place where women are quietly reassessing the terms of participation.

The United States has no federal requirement for paid vacation or paid parental leave, according to the U.S. Department of Labor. Access to rest depends heavily on employer, income level, and industry.

In contrast, many peer nations mandate paid leave as a baseline. New Zealand, for example, guarantees four weeks of paid annual leave for most employees, along with paid parental leave, as outlined by Employment New Zealand. Similar standards exist across much of Europe.

These policies reflect a different understanding of productivity. Rather than maximizing output in the short term, they prioritize longevity over decades.

For women balancing paid work with caregiving, this difference can determine whether a career feels sustainable or extractive.

Endurance can produce results for a while. Sustainability determines who stays in the system.

Rights, Stability, and Long-Term Planning

Long-term planning requires trust that systems will function and protections will hold.

In the United States, changes to reproductive healthcare access have introduced geographic uncertainty. Care availability varies by state, and legal landscapes continue to shift. This uncertainty often shows up not as protest, but as quiet contingency planning.

- Where could I reliably access care?

- What happens in an emergency?

- How stable are these protections over time?

In countries where reproductive healthcare is broadly protected, that layer of uncertainty is reduced. Planning becomes simpler. The mental energy spent on worst-case scenarios can be redirected elsewhere.

Seeing Alternatives Makes Trade-Offs Visible

One reason this conversation has gained momentum is that alternatives are increasingly visible.

Remote work has expanded geographic options. Information about healthcare systems and work culture abroad is widely accessible. Stories circulate not as advocacy, but as comparison.

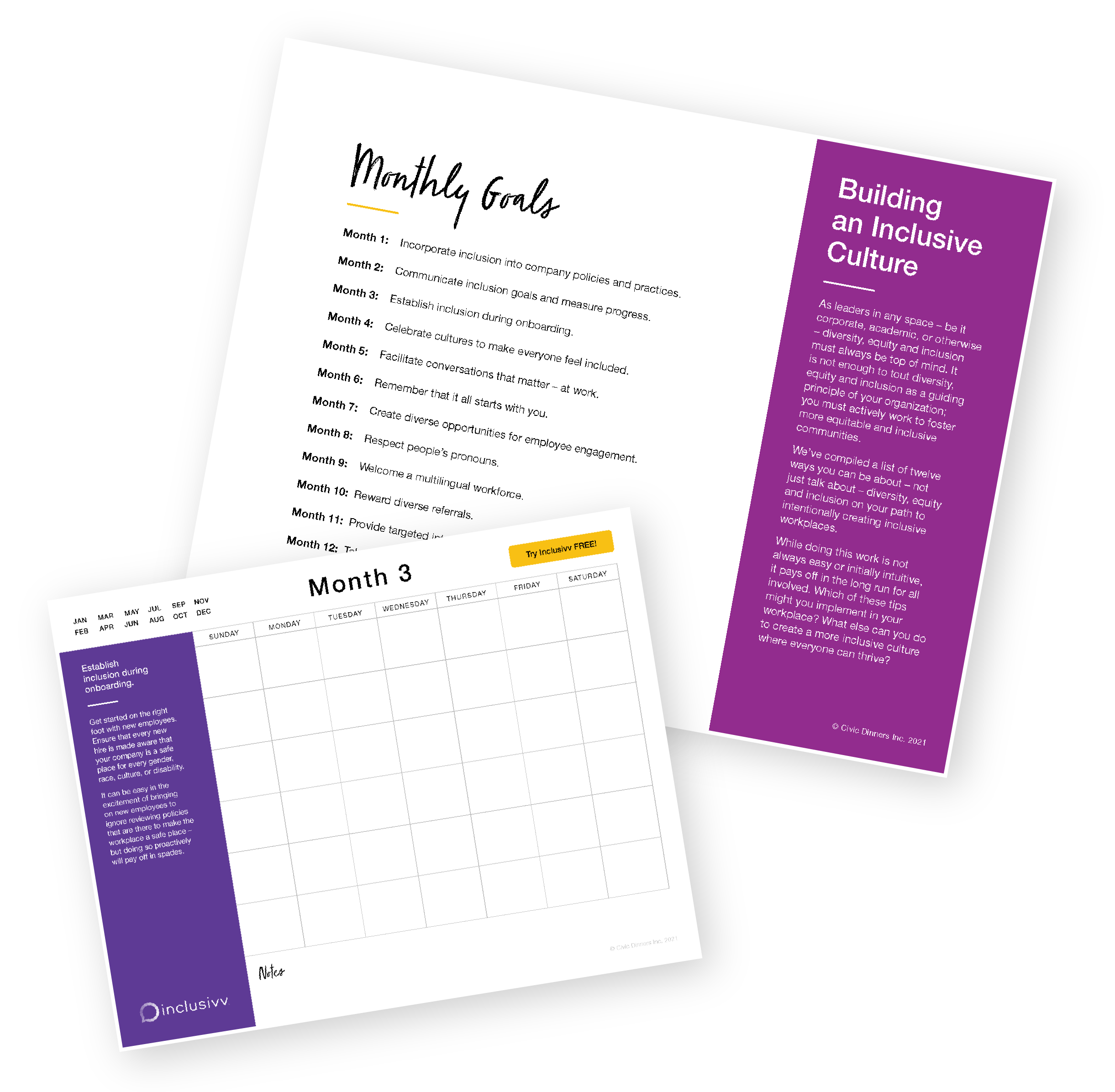

At Inclusivv, this shift is grounded in lived experience. Our company’s CEO has already relocated internationally, gaining firsthand insight into how different systems around healthcare, safety, work, and rest shape daily life. That perspective reinforces what many women are discovering independently: systems are choices, and different choices produce different outcomes.

Once those differences are seen up close, certain trade-offs become harder to accept as inevitable.

A Retention Issue, Not a Loyalty Test

From an economic and social standpoint, this moment matters.

Women between 15 and 44 make up a significant share of the workforce and shoulder a disproportionate share of unpaid caregiving labor. When large numbers of them feel uncertain about staying, the ripple effects extend outward. Workforce participation shifts. Talent retention suffers. Community stability weakens.

Organizations understand this dynamic instinctively. When retention drops, leaders examine conditions. They do not assume employees are simply restless. They ask what has changed.

What Listening Could Look Like

Listening does not require a single sweeping reform. It requires acknowledging that quality of life is shaped by systems, not just individual resilience.

It means asking whether healthcare reduces fear or adds to it.

Whether childcare supports participation or limits it.

Whether work culture allows people to recover and continue.

Whether safety and rights enable long-term planning.

These are not fringe concerns. They are foundational.

When people imagine leaving, they are often responding to what feels missing, not what they want to abandon.

A Moment Worth Taking Seriously

The fact that nearly forty percent of young women imagine life outside the United States should not be read as a verdict. It is feedback from people deeply invested in the future.

It reflects a desire for stability, safety, and systems that support the realities of modern life. It highlights the gap between what people are asked to manage individually and what could be shared collectively.

Listening to that feedback does not require agreement on every solution. It requires acknowledging that the questions being asked are reasonable.

Because wanting a life that feels structurally supported is not radical.

It is human.

And the way those questions are answered will shape who stays, who leaves, and what kind of future feels possible.

.png)